RISK ASSESSMENT, POLICY AND RISK COMMUNICATION

Online Course

INDEX

1. Introduction

Any substance can induce toxic effects under certain circumstances. These circumstances may include the chemical form of the compound, the route of entry, or the dose, among others.

Risk assessment serves to evaluate whether, under specific circumstances, a compound, a xenobiotic, may be toxic to a specific population. Therefore, the ultimate goal of risk assessment is to estimate the probability that a xenobiotic will produce adverse effects under certain exposure conditions.

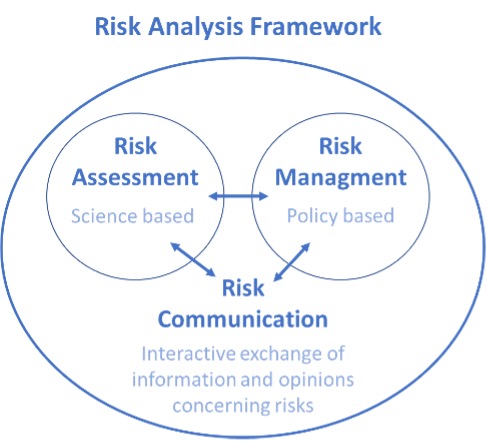

Risk assessment is a purely scientific stage and is one of the three pillars of risk analysis (Figure 1). The other two pillars correspond to risk management, which involves the application of regulatory and control policies, and risk communication, which should be interactive between scientists, managers, and the general public.

The ultimate goal of human health risk assessment is to protect human health. However, considering the production, presence, use, and disposal of many chemical compounds that may become environmental pollutants risks to living organisms in the environment or to the environment itself can also be studied. In this case, it is called environmental risk assessment.

The present teaching material is focused on human health, however it is important to note that the mere presence of potentially toxic xenobiotics in the environment -air, water, soil, and living organisms- constitutes a threat to human health if no maximum limits are set.

Indeed, nowadays the focus is to move to the One Health approach which recognizes the interconnection between human, animal, and environmental health. Although initially focused to zoonotic diseases, it also covers exposure to chemicals.

For more information on the One Health concept you can access the following video that details the collective efforts of five EU agencies to integrate human, animal, plant, and environmental health strategies in response to pressing challenges like climate change, disease outbreaks, and environmental pollution. The five EU agencies involved are the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), and the European Environment Agency (EEA).

You can also access the website of WHO.

Introduction to Risk Assessment

This introductory problem-based learning (PBL) activity focuses on fundamental concepts in risk perception, assessment, and management. It is designed to help students understand how risks are identified, perceived by individuals and society, and managed through policy and communication strategies.

The case study encourages students to reflect on everyday situations that may involve health or safety risks—such as mobile phone use while cycling—and to analyse how individuals and governments respond to these risks. Students explore differences in personal risk perception and how this influences behaviour, drawing comparisons between countries and regulatory approaches.

Throughout the activity, students are introduced to a structured risk management model. They complete individual and group exercises, such as:

- Identifying risks in real-life scenarios based on images and personal experience;

- Ranking perceived risks using a matrix to compare likelihood and impact;

- Discussing differences in perception and cultural or legal responses;

- Analysing examples of public health policy, including cervical cancer screening protocols and water safety assurance.

This PBL scenario promotes critical thinking, collaborative learning, and a holistic understanding of how risk is addressed in public health and environmental contexts. It is an ideal starting point for students in toxicology-related programmes who are new to the concepts of risk assessment, policy development, and science-based communication.

Download complementary files:

(*) This file is for use by tutors/teachers and is password protected. If you are a tutor/teacher interested in using this case study, please contact us to get the password.

1.1. The concept of risk

There are two elements that determine the risk to a specific population: exposure and hazard.

Hazard refers to the toxic properties a specific xenobiotic possesses. For instance, it may exhibit significant liver toxicity, act as a neurotoxic agent, cause tumors, etc.

Exposure is what enables contact between the xenobiotic and humans, and this can occur through different routes, as explained in the following section on exposure.

For risk to occur in a specific population, exposure to an agent capable of causing toxicity under those exposure conditions is necessary. The risk increases as exposure and hazard increase. Thus, risk can be simplified into an equation with two factors: exposure and hazard.

Risk = Hazard x Exposure

If exposure is zero, even if the compound is highly hazardous, the risk -the probability of an adverse effect – will be zero or very low. Conversely, if the compound is almost innocuous -requiring very high concentrations to produce an adverse effect- the risk will also be very low because it will be unlikely to reach toxic exposure levels.

Let’s see some specific examples to understand the concept better:

- Carbon monoxide, for example, is a highly toxic gas and thus very hazardous. Its mere presence constitutes a hazard because even low concentrations can be fatal to humans. However, if appropriate safety measures are taken to avoid exposure to this gas, the risk is very low.

- Amanitin, a toxin produced by the poisonous mushroom Amanita phalloides, is highly hazardous, causing liver toxicity that can lead to death or require a liver transplant. The risk of poisoning in some countries, particularly in areas where people are accustomed to foraging for mushrooms, is not zero, as the lack of knowledge and recklessness of some gatherers cause acute poisonings each year.

2. Risk Assessment

As mentioned, risk assessment involves estimating the likelihood of adverse effects occurring under certain exposure conditions. The process consists of four phases:

- Hazard Identification: Study of the adverse effects of a xenobiotic.

- Hazard Characterization: Evaluation of the dose-response relationship to determine the relationship between exposure levels and the incidence or severity of adverse effects.

- Exposure Assessment: Determining the concentrations/doses to which human populations are exposed.

- Risk Characterization: Integrating all previous data to estimate the incidence and severity of adverse effects likely to occur in an exposed population.

2.1. Hazard identification and characterization

2.1.1. Hazard identification

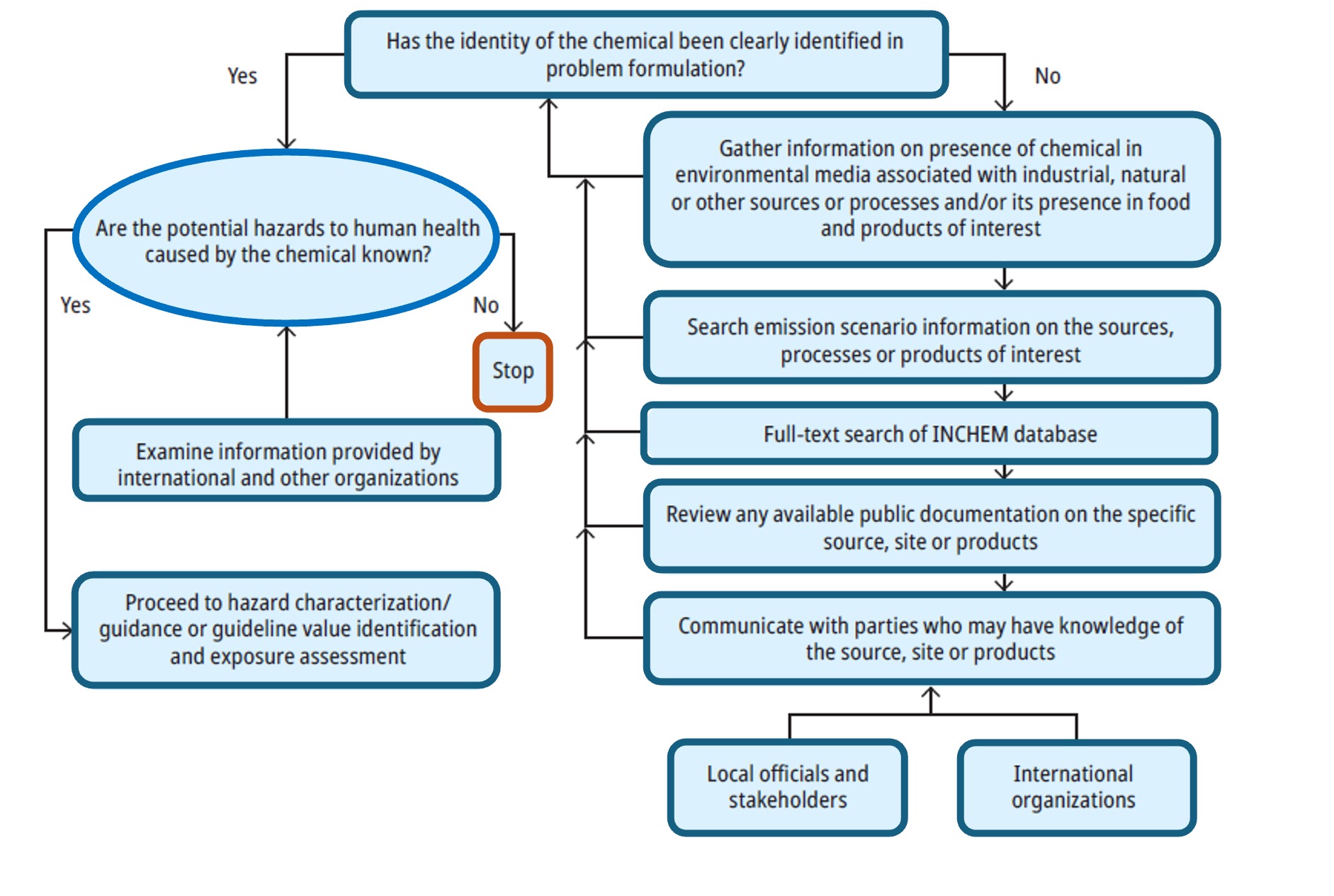

Hazard identification is generally the first step in a risk assessment and is the process used to identify the specific chemical hazard and to determine whether exposure to this chemical has the potential to harm human health.

The approach recommended by the World Health Organization WHO is to establish the identity of the chemical of interest and to determine whether the chemical has been considered hazardous by international organizations and, if so, to what degree.

The process for gathering information in support of hazard identification proposed by WHO is illustrated in Figure 2.

As an example, this preliminary information can be gathered from:

- A wide variety of toxicity assays using different experimental systems to gather information that progressively defines the type of toxicity a particular xenobiotic can cause and the conditions under which it occurs. These methodological tools will be explained throughout this text, especially in the hazard characterization, as well as the toxicity parameters obtained and used for risk assessment and/or preventive measures. The advantage of these toxicity studies is that they are conducted under controlled conditions, and the design always allows for the establishment of a dose/concentration-response/effect relationship. The disadvantage is that these studies can only be conducted on animal models or in vitro or ex vivo experimental systems, and their extrapolation to humans is necessary.

- Data on humans can only be obtained from accidental poisonings—typically acute and with unknown doses—from clinical trials during drug development, or from epidemiological studies where both exposure and toxicity are estimated, often with a high degree of uncertainty.

- Computational tools have also been developed to predict the toxicity of new compounds based on known data from other substances. This is a promising field in development, but for now, it is mainly used as an initial screening tool as it does not replace a complete toxicological characterization through toxicity assays, which are required by regulatory agencies in various fields.

2.1.2. Hazard characterization and health-based guidance values (HBGV)

2.1.2.1. Hazard characterization

Hazard characterization is the qualitative and/or quantitative assessment of the potential of a chemical to cause adverse health effects as a result of exposure.

According to WHO “an adverse effect is defined as a change in the morphology, physiology, growth, development, reproduction or lifespan of an organism, system or (sub)population (or their progeny) that results in an impairment of functional capacity, an impairment of the capacity to compensate for additional stress or an increase in susceptibility to other influences. To discriminate between adverse and non-adverse effects, consideration should be given to whether the observed effect is an adaptive or trivial response, transient or reversible, of minor magnitude or frequency, a specific response of an organ or system, or secondary to general toxicity”.

Hazard characterization is therefore the toxicological evaluation of the compound.

In experimental toxicology, in vitro and in vivo models can be used for hazard characterization. Whether usingin vivo or in vitro models, deciding the doses or concentrations to be tested and preparing them are key aspects of the experimental design. This allows for an unequivocal relationship between a given dose or concentration and a toxic effect. In these situations, exposure is a controlled factor with no uncertainties. Toxicology studies typically involve administering a known and chosen dose of a pure substance to an animal through a route of administration selected by the investigator. The exposure level is the chosen dose, which would be the independent variable. What is more difficult to quantify is the concentration of xenobiotic reaching each organ, which is the internal dose and is ultimately the most important. In all cases, a dose-response assessment must be conducted, therefore there is the need of testing at least three different doses or concentrations in each experiment.

In an in vitro experimental system, the situation is even simpler. Cells are exposed to a specific concentration of xenobiotic in the culture medium in which they are grown. The exposure concentrations are also determined during the experimental design. Even in this case, the amount of xenobiotic absorbed by the cells can vary depending on the concentration, the number of cells in the culture, and the cells’ absorption system, which may involve simple diffusion, active transport, or pinocytosis. For more information on cell culture techniques you can visit the following project website (RALDE) where you can find an online practical and a game regarding cell culture technique.

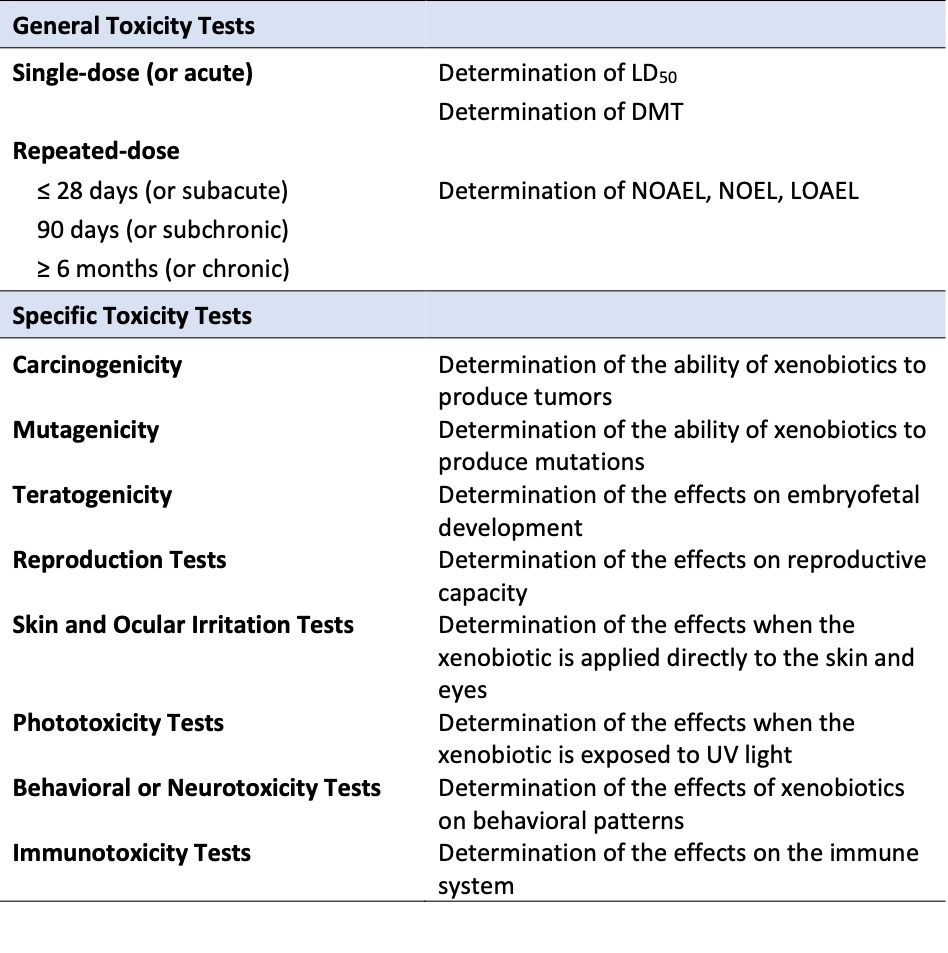

Toxicological studies include a battery of tests conducted in in vitro, in vivo, and increasingly in silico models, which allow for the toxicological characterization of new compounds. In general, toxicity assessment methods can be classified into two broad categories: general toxicity tests and specific toxicity tests (Table 1).

The first category, general toxicity studies, encompasses all tests designed to evaluate any type of effect on the functional or morphological aspects of various systems or organs. Within this category, tests differ in terms of the total duration of the study and the depth with which general toxicity in animals is critically evaluated.

The second category of tests includes those specifically designed to evaluate particular types of toxicity in detail. Repeated-dose toxicity tests do not detect all forms of toxicity but can reveal some toxic effects and highlight the need for more specific studies. Additionally, the intended use of the compound in question may require assessing its safety concerning certain specific forms of toxicity, such as skin and eye irritation tests for cosmetics.

For more information, you can access this lecture in the Advanced Courses of the Tox4Learn project.

As mentioned, the dose-response evaluation is obtained from toxicity studies, but these face the challenge of extrapolation from in vitro or in vivo studies to humans. Three major unknowns arise when predicting a xenobiotic’s behavior in humans based on data obtained from animal toxicity studies:

- Does it have the same effect at equivalent doses in humans as in animals (e.g., rats)? Two key aspects must be considered: a) absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) processes of the compound should be similar in both species; b) the mechanism of action in the animal species should be relevant to humans. Indeed, in toxicological phenomena, three major phases are distinguished: exposure, toxicokinetics, and toxicodynamics. Absorption is the process through which the toxin enters the bloodstream and can be distributed throughout the body, leading to the transit processes of the xenobiotic in the body, or toxicokinetics (including metabolism, distribution and excretion). Toxicodynamics refers to the set of reactions that take place from the moment the toxin comes into contact with its biological receptor, which may be specific or non-specific; this is mainly related to the mechanism of action of the xenobiotic.

- What happens at low doses? What about doses that humans are actually exposed to? Toxicity studies, by definition, must reach toxic doses, which are sometimes much higher than what is encountered in real human exposure situations.

- What about more sensitive populations, such as infants, pregnant women or elder populations? Toxicity studies do not account for these aspects. However, risk assessments must consider more vulnerable populations. In this video these aspects are discussed in more depth.

Individual Susceptibility and Pharmacogenomics

This thought-provoking PBL case explores how genetic variability in drug metabolism can lead to serious, even fatal, consequences. It highlights the importance of personalized medicine and pharmacogenomics in risk assessment, especially when it comes to vulnerable populations like newborns.

The case is based on the real-life death of an infant in Toronto from opioid toxicity, traced back to codeine use by the breastfeeding mother. Unbeknownst to her or her physicians, she was an ultra-rapid metabolizer of codeine due to carrying multiple copies of the CYP2D6 gene. This genetic trait led to dangerously high levels of morphine in her breast milk, ultimately causing the baby’s death.

Students are asked to analyze this case and address the following key themes:

- How genetic polymorphisms like CYP2D6 influence drug metabolism and toxicity;

- The role of pharmacogenetic testing in predicting individual susceptibility to adverse effects;

- Clinical and ethical implications of prescribing drugs without considering genetic variability;

- How other factors—such as diet, co-medication, or environmental exposures—may influence risk.

Part of the case includes data analysis: students evaluate CYP2D6 genotyping results from a group of university students, calculate phenotype distributions, and compare the data to expected frequencies from the literature. They are encouraged to explain potential discrepancies and reflect on the implications for public health and clinical decision-making.

This interdisciplinary PBL is ideal for students of toxicology, pharmacology, biomedical sciences, and public health. It encourages the integration of molecular biology, clinical toxicology, and ethical reasoning in the context of real-world health risks.

Download complementary files:

(*) This file is for use by tutors/teachers and is password protected. If you are a tutor/teacher interested in using this case study, please contact us to get the password.

Epidemiological studies seek to obtain both exposure and toxicity data in humans and establish causal relationships using statistical tools that help correlate dose and response. However, epidemiological studies require a population to be exposed to the compound as it naturally occurs (not deliberately exposed as in clinical trials for example).

Exposure to urban incinerator fumes – design your own biomonitoring study for exposure assessment

In this case study you will explore the types of biomarkers to assess to characterize the hazard and the health effects of the exposure. Consider if certain groups are more susceptible to the exposure?

2.1.2.2. Health-based guidance values

In all cases the final aim of toxicological characterization is to carry out the aforementioned dose-response assessment focused on identifying the Point of Departure (POD) for health effects in critical studies. The POD is therefore the point on a dose–response curve established from experimental data used to derive a safe level.

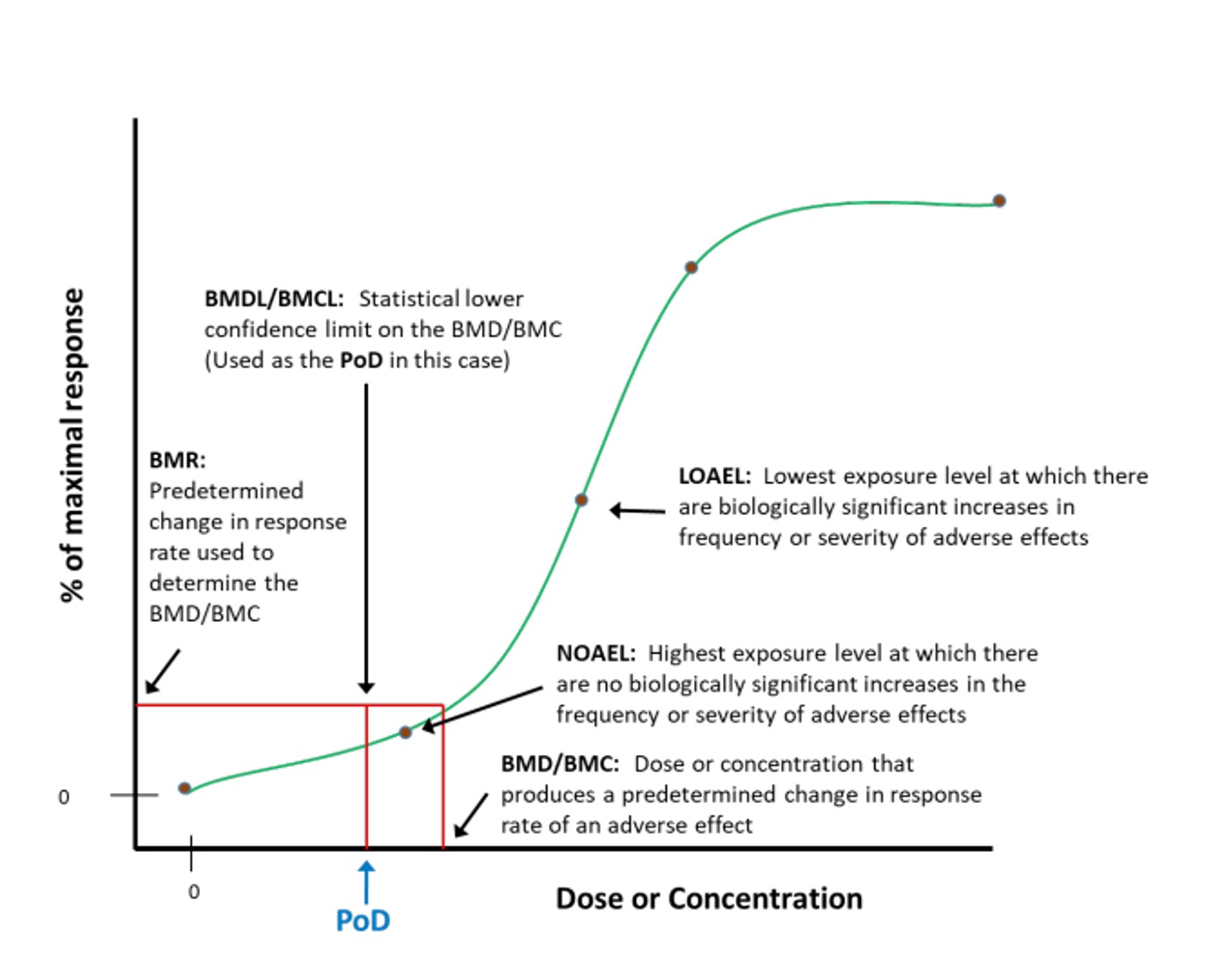

Some of the most relevant POD are the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL), Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level (LOAEL) or the benchmark dose (BMD). They are critical concepts used to evaluate the safety and potential risks of chemical substances and are obtained in toxicological experiments.

A) No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) and Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level (LOAEL)

The NOAEL is defined as the highest dose or exposure level of a substance at which no adverse effects are observed in the exposed population, under defined study conditions. It is established through the previously toxicological studies mentioned where various dose levels are assessed. The NOAEL is an essential reference POD for determining safe exposure limits in human; healthbased guidance values, such as the Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) or Reference Dose (RfD).

The LOAEL refers to the lowest dose or exposure level at which adverse effects are observed in the exposed population. When a NOAEL cannot be determined, the LOAEL is often used as the starting point for risk assessment.

A key Distinction between them is that the NOAEL represents the threshold below which adverse effects are not detected, while the LOAEL identifies the minimum dose where adverse effects begin to manifest.

Both parameters are fundamental for establishing safety margins and regulatory guidelines in the assessment of chemicals, drugs, and environmental toxins.

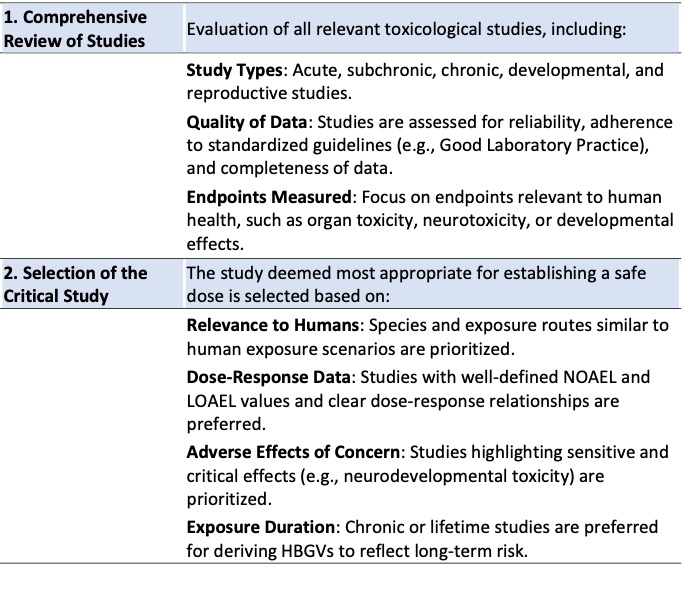

Both parameters are established through carefully designed toxicological studies aimed at identifying the highest dose of a substance that does not produce any significant adverse effects under the conditions of the study. Normally NOAEL/LOAEL used for establishing are derived from general toxicity studies (repeated dose studies), however in certain circumstances NOAEL/LOAEL can also be derived from specific toxicity studies (genotoxicity, carcinogenicity) or from epidemiological studies. The process involves several key steps (Table 2).

It is important to note that NOAEL (or LOAEL) are derived for each individual experiment.

Below you can find an example of a NOAEL derived from a chronic toxicity study of a test compound:

- Doses Administered: 0 mg/kg (control), 10 mg/kg, 50 mg/kg, and 100 mg/kg per day.

- Observations: Liver toxicity was observed at doses of 50 mg/kg and higher. No adverse effects were observed at 10 mg/kg.

- NOAEL: The NOAEL is determined to be 10 mg/kg (therefore the LOAEL is 50 mg/kg- however LOAEL in not used when a NOAEL is available).

B) Benchmark Dose Method

The benchmark dose method is a procedure used to obtain values based on a starting or reference dose (“benchmark”), without using NOAEL values. It involves fitting all available experimental data to a dose-response curve with specific confidence intervals. This is a very labor-intensive process that requires substantial computational tools. The aim is to find the dose-response curve model, mathematically characterized, that best fits the available data. In this way, unlike NOAEL-based approaches, a dose-response curve is obtained considering all or most of the experimental results. Additionally, the variability associated with the dose-response curve is quantified through confidence intervals (Figure 3).

A specific response level (benchmark response level) is then defined, typically 10%. Finally, the dose corresponding to the lower confidence limit for that response level is calculated, which becomes the benchmark dose.

For example, in a study examining the effect of a pesticide on liver toxicity. If a 10% increase in transaminases over the background level is chosen as the BMR:

- Dose-response data are collected across several dose levels and/or studies.

- Models are fit to the data, and the dose corresponding to the 10% increase is determined as the BMD.

The advantages of this method include: a) introducing a measure of variability, such as confidence intervals, into the dose-response curve, which, in turn, is obtained by considering many experiments rather than just one; b) calculating the benchmark dose within the range of observable experimental responses, without the need to extrapolate to lower doses.

C) Derivation of Health-Based Guidance Values

When only animal data is available and it is necessary to protect the population from possible adverse effects, preventive measures are taken to minimize the risk. This involves recognizing the typical pattern of toxic effects of the compound, assessing the relevance of that toxic potential in humans, and implementing measures to reduce exposure—either by prohibiting or restricting the use of the compound or by controlling its presence in food, for example (see the section on risk management and communication).

There are at least two situations where such measures are advisable, due to the impossibility of conducting risk assessments based on human data: a) chemical products for which it is very unlikely to have human data available, and b) toxic effects that require extensive, long-term human exposure to gather data, such as carcinogenic or reproductive effects.

As mentioned before, NOAEL (or LOAEL) are derived for each individual experiment carried out for a certain chemical. Thus, when multiple toxicological studies are available, the process of selecting the most relevant NOAEL for human health risk assessment and deriving a health-based guidance value (HBGV) follows a structured and systematic approach (see Table 3). Normally the Weight of Evidence (WoE) approach is followed, by taking into account consistency across studies (repeated findings in multiple studies and species), study quality (higher weight is given to robust, well-designed studies) and outliers or conflicting data (these are carefully evaluated in the context of overall evidence).

This ensures that the assessment is robust, evidence-based, and protective of public health.

Once POD is determined (NOAEL of the critical study or the BMD), the HBGV can be calculated.

Some of the most used HBGV are the Reference Dose (RfD) and the Acceptable/Tolerable Daily Intakes (ADI/TDI). The term Reference Concentration (RfC) is used for compound to which humans are exposed via inhalation. All of these terms define the daily intake of a chemical compound, which, over a lifetime, poses no appreciable health risk, based on the data available at the time.

Normally ADI is used for substances that need pre-market authorization such as additives and pesticides. In case, of contaminants the Tolerable daily intake (TDI) is the correct term. These two terms are generally used by World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). The term RfD is preferred by the U.S Environmental Protection Agency.

Reference doses and ADIs are calculated from NOAEL or BMD values by dividing them by safety factors, also known as uncertainty factors, and modifying factors, which are not always applicable.

ADI or RfD = NOAEL or BMD / UNCERTAINTY FACTORS

Uncertain factors are used to address potential uncontrolled variations that lead to uncertainties in risk characterization.

Uncertainty factors generally range from 0 to 10; by default, a value of 10 is applied. A variable number of these factors may be used for different purposes:

- extrapolation from animal data to humans,

- accounting for a more sensitive population group,

- extrapolating results from short-term studies to chronic exposure,

- when only LOAEL data is available instead of NOAEL,

- to generally mitigate any experimental limitations.

- when knowledge of the compound’s mechanism of action and toxicokinetics or the relevance of the animal response to human health is not clear.

Example:

Supose two studies on a chemical show the following results:

- Study A (3 months study in rats): NOAEL = 10 mg/kg. LOAEL = 20 mg/kg

- Study B (28 days mouse study): NOAEL = 15 mg/kg. LOAEL = 25 mg/kg

The NOAEL from Study A is selected as the POD because it is lower and derived from a chronic study, which is more relevant for long-term human exposure. An uncertainty factor of 1000 is applied (x10 to account for interspecies variability, x10 for intraspecies variability, and x10 for study duration). The HBGV is calculated as:

HBGV = 10 mg/kg bw / (10 x 10 x 10) = 0.01 mg/kg

This value is then used for regulatory and safety purposes to ensure public health protection.

2.1.2.3. In vitro studies in hazard characterization

In the context of risk characterization, in vitro studies play a critical role in assessing the potential adverse effects of chemical compounds on the environment or health. Specifically, in vitro genotoxicity assays are essential for determining whether a compound has the potential to damage the genetic material of organisms. These studies evaluate specific indicators of genotoxicity, such as DNA mutations, chromosomal aberrations, or damage to genetic material, using simplified and controlled

Currently, there is a growing emphasis on the use of in vitro assays in risk characterization, reflecting a shift towards reducing animal testing and promoting the development of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs ). These methodologies encompass a broad range of innovative tools and strategies, including in vitro systems, computational models, high-throughput screening, and omics technologies, which aim to improve the prediction of chemical hazards while minimizing reliance on traditional animal studies. NAMs are designed to provide more accurate, efficient, and ethical approaches to risk assessment by leveraging advancements in biology, toxicology, and computational science. This shift highlights the global commitment to modernizing risk assessment processes in line with scientific innovation and ethical considerations.

Therefore, NAMs are useful tools for mechanistic toxicology that can provide information for Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs ). The AOPs provide a framework linking a chemical’s molecular interaction (Molecular Initiating Event) to adverse health or environmental outcomes via measurable Key Events.

Together, AOPs and NAMs support risk assessment by improving our ability to predict adverse outcomes using mechanistic, human-relevant, and high-throughput data, increasing efficiency and ethical alignment in evaluating chemical safety.

For more information on NAMs and AOPs you can watch the following lectures:

2.2. Exposure assessment

Exposure is one of the two main elements of risk assessment, along with toxicity. Therefore, quantifying exposure is crucial. However, in some situations, this quantification is highly complex, and although exposure estimates can be made, they often come with a high degree of uncertainty.

According to WHO, exposure assessment “is used to determine whether people are in contact with a potentially hazardous chemical and, if so, to how much, by what route, through what media and for how long”.

For a toxic substance to pose an actual risk to health, it must be present in the environment and come into contact with the organism. Quantification can be carried out by quantifying the concentration in the environment, food, and beverages and estimating the amount of toxin ingested, inhaled, etc. This approach is focused in measuring the external exposure. Furthermore, exposure can be evaluated by quantifying the xenobiotic or its metabolites in blood and urine. In this case, internal exposure is being measured, which is the actual focus of interest.

If such measurements are taken regularly over a long period, it is called monitoring, which can be either environmental (external exposure) or biological (internal exposure), also known as biomonitoring.

When dealing with a xenobiotic that we may be unintentionally exposed to due to its presence as an environmental contaminant, the level of exposure will depend on the amount of toxin released and the fate of the toxin in the environment. Therefore, quantifying exposure requires determining the production of a substance and its environmental kinetics (dispersion, transformation, and deposition). These production and environmental kinetics phases determine the physical availability of the toxin, i.e., the amount of the active form available for penetration.

Except in the pharmaceutical sector where humans are intentionally exposed to medicines, quantifying exposure is very difficult and is the process that generates the highest degree of uncertainty. Exposure quantification in humans is carried out based on analytical data showing the presence of a xenobiotic in certain matrices, followed by calculations to estimate the dose of external or internal exposure.

To do this, the following scenario is defined: i) which exposure routes are relevant (oral, dermal, inhalation); ii) how long the exposure lasts (hours, days, years); iii) how frequently it occurs (once a day, every two hours, etc.).

Risk assessment considers populations, such as inhabitants of a specific geographic area or country consuming water with high arsenic content, workers in the asbestos industry, or pregnant women consuming mercury-contaminated fish. Therefore, it is necessary to make average exposure estimates based on water consumption, working hours in the industry, and fish consumption, respectively, according to the three examples mentioned. Analytical data used to make exposure estimates can be obtained through various means:

- Measuring the contaminant’s presence in water or contaminated food. From questionnaires, consumption patterns in populations can be determined, and population exposure estimates can be made.

- In work environments, direct measurements of contaminants in the workplace air (air inhaled by workers) are usually taken, and sometimes simple equipment can take measurements at different times during the workday.

In some cases, certain xenobiotics or their metabolites can be analyzed in biological samples (blood, hair, urine, saliva), serving as biomarkers of exposure.

In the environment, contaminants are usually measured directly in air, food, water, soil, or animal/plant species.

Occupational Exposure to Hazardous Chemicals

This PBL case study addresses chemical exposure in the workplace, focusing on the health risks faced by professional painters and the evolving regulatory responses aimed at protecting workers. Based on a realistic scenario, the case highlights both individual and institutional responsibilities in identifying, managing, and communicating chemical risks.

Students are introduced to Mr. Bax, a 52-year-old house painter who has worked with solvent-based paints for over three decades and is now experiencing symptoms such as dizziness and headaches. Despite occupational safety advice on proper ventilation, implementation was inconsistent. Following regulatory changes driven by health and environmental concerns, solvent-based paints have been replaced by safer water-based alternatives—yet complaints persist.

Students step into the role of a risk manager, Yannick, who is tasked with assessing chemical risks in the workplace. His investigation involves:

- Reviewing past practices and current regulations (e.g. Working Conditions Act);

- Consulting with occupational health professionals and employees;

- Considering previous cases involving hazardous substances (such as chromium-6 in military settings);

- Evaluating communication and prevention strategies within the organisation.

This PBL encourages students to explore:

- Risk identification and exposure assessment in real-life occupational settings;

- The impact of chemical regulation on professional practices;

- Ethical and scientific responsibilities in protecting worker health;

- Effective risk communication and organisational change.

It provides an ideal learning environment for students in toxicology, occupational health, or environmental sciences, while fostering critical thinking, policy literacy, and stakeholder engagement.

Download complementary files:

(*) This file is for use by tutors/teachers and is password protected. If you are a tutor/teacher interested in using this case study, please contact us to get the password.

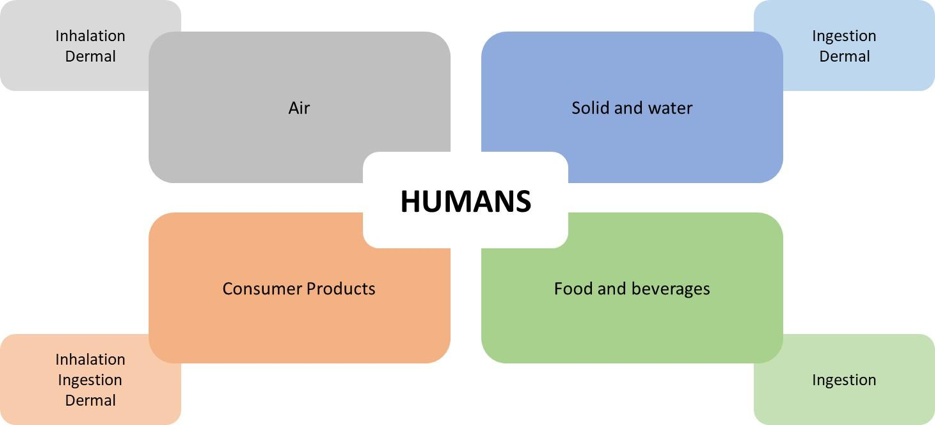

Pathways of exposure

According to WHO “pathway of exposure refers to the physical course taken by a chemical as it moves from a source to a point of contact with a person (for example, through the environment to humans via food)”.

The appearance of a specific contaminant in a particular environmental or food matrix depends on its production/emission, i.e., the amount synthesized or formed, and its release into the environment. This release occurs in the form of emissions or discharges, depending on whether it is released into the air, water, or land, potential exposure media. Production or emissions can be either natural or anthropogenic.

Routes and types of exposure

According to WHO, “route of exposure refers to intake through ingestion, inhalation or dermal absorption. The exposure routes may have important implications in the hazard characterization step, as the danger posed by a chemical may differ by route”.

The natural routes of entry for xenobiotics include oral (o), inhalation (i), dermal (d), and transplacental routes. Some compounds can easily cross the placenta. For example, lead reaches very similar concentrations in the fetus and the mother.

Some compounds can enter through various routes. For example, cadmium can be ingested with food and drink, but it can also be inhaled with cigarette smoke.

There are also extraordinary routes of exposure such as intravenous (iv), subcutaneous (sc), intramuscular (im), and intraperitoneal (ip), among others. These are primarily used in pharmacotherapy or drug use/abuse.

Exposure to a toxic agent can be intentional or voluntary, or it can be unintentional or accidental.

Intentional exposure occurs in the following situations:

- In the use of narcotics and drugs of abuse, where individuals voluntarily expose themselves to known or unknown doses of drugs, sometimes with uncontrolled impurities and often in mixtures with other drugs and alcohol and/or tobacco. In such cases, determining the true dose of exposure is not easy.

- In pharmaceuticals, normally known doses of medications are administered. A different situation arises when a person is exposed to a drug overdose, either voluntarily (self-harm) or involuntarily (medication errors). In cases of medication poisoning, it is also challenging to determine the dose of exposure. In the case of pharmaceuticals, a strict standardized and regulated safety assessment is carried out before commercialization.

Unintentional exposure can occur in various ways.

The most common is through food, drinking water, or air contamination. In such cases, it is difficult to determine the nature of the contaminant and mixtures to which an organism is exposed, and even more challenging to quantify exposure.

Exposure through food.

Besides nutrients, food contains many organic and inorganic compounds that can have either beneficial or adverse effects. Some are natural, while others are synthetic. Among the natural substances, some are part of the food itself, while others are contaminants. The substances present in food that can have adverse health effects include:

- High nitrate concentrations in vegetables, especially spinach. Excessive use of nitrogen fertilizers can lead to elevated nitrate levels in vegetables. Nitrates can be converted into nitrites by nitrate reductases found in bacteria throughout the gastrointestinal tract. These nitrites can react with secondary amines, leading to the formation of nitrosamines, which are potent carcinogens.

- Mycotoxins in food intended for human or animal consumption. Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites produced by fungal species that grow on food or raw materials during growth or storage, causing adverse effects on human health.

- Pesticide residues present in food, which remain as a result of poor application practices in the field, or due to environmental contamination, thus entering the food chain.

- Heavy metals and other compounds present in highly contaminated soils, such as cadmium, mercury, or polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

- Veterinary drug residues in meat, which can remain in food if antimicrobial treatments are not applied correctly, often due to overuse to enhance livestock productivity.

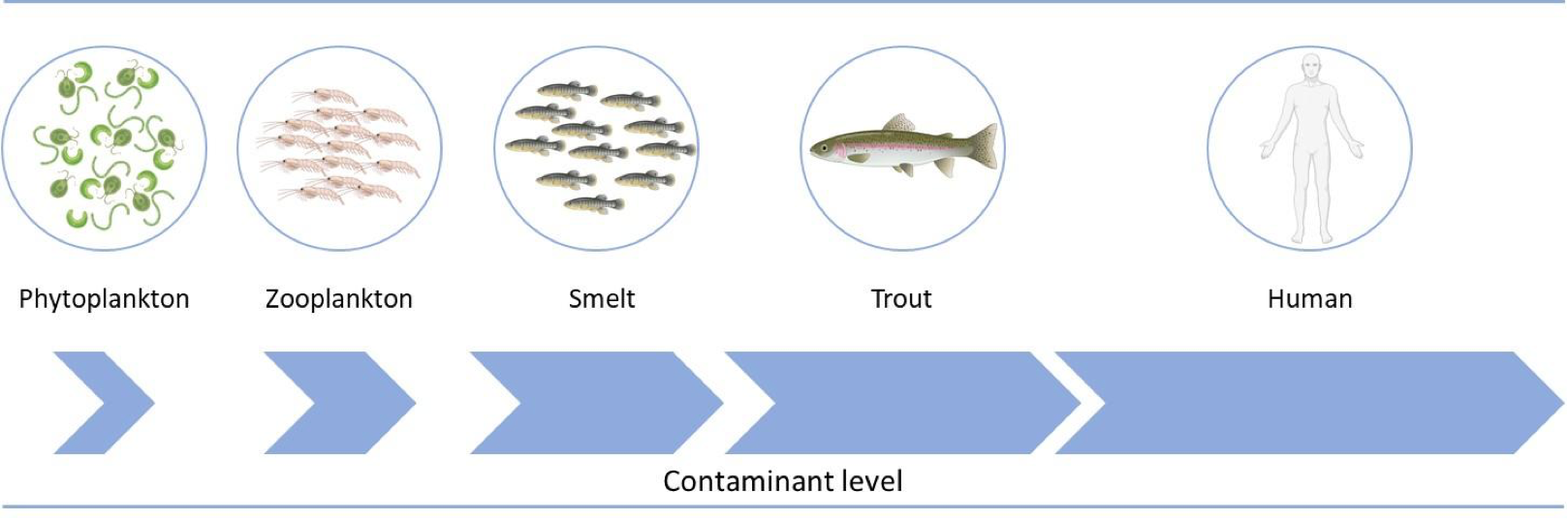

All these substances are contaminants that may be present in food, and humans can be exposed without realizing it. Moreover, some xenobiotics present in the environment that do not degrade through physical or biological means can accumulate in organisms. This occurs especially with highly liposoluble compounds, such as DDT and other organochlorines, which are very resistant to metabolism, and thus are considered persistent organic pollutants (POPs). These compounds undergo bioaccumulation and biomagnification. Bioaccumulation refers to the progressive increase in the amount of a chemical compound in a living organism, while biomagnification is the process by which the amount of a chemical compound increases in organisms higher up in the food chain. As a result, the predator at the top of the food chain will have the highest concentration of the compound (Figure 5).

On the other hand, some substances are intentionally added to food for various purposes. These are food additives of various types, such as preservatives, colorants, and sweeteners. They may have adverse effects but, as in the case of pharmaceuticals, are highly studied and regulated.

Food Safety and Public Health

Foodborne illnesses are a significant concern for public health authorities, industries, and consumers alike. This PBL case study explores the challenges of detecting, managing, and communicating risks associated with microbiological and other types of food contamination.

The case begins with a provocative question—MacDeath?—inspired by a real-life outbreak of E. coli infections linked to fast-food burgers, which tragically resulted in at least one death. Students are invited to examine how such outbreaks are identified, how causality is determined, and what systems are in place to prevent future incidents.

Participants are encouraged to think critically about:

- The diversity of biological hazards in food (e.g. bacteria like E. coli, viruses like Norovirus, prions such as those involved in BSE, and mycotoxins from fungi);

- The complexity of tracing contamination sources and enforcing food safety protocols;

- The roles and responsibilities of health agencies, food producers, and regulatory bodies;

- The importance of risk communication in maintaining public trust and promoting informed decision-making.

This PBL scenario stimulates discussion around real and perceived risks, individual susceptibility, and societal reactions to foodborne hazards. It is ideally suited for students studying toxicology, food safety, microbiology, or public health, providing a realistic and interdisciplinary perspective on risk assessment and management in the food sector.

Download complementary files:

(*) This file is for use by tutors/teachers and is password protected. If you are a tutor/teacher interested in using this case study, please contact us to get the password.

Exposure through water.

Humans and any living organism can be exposed to a wide variety of substances through. It is necessary to differentiate between surface water and drinking water.

- Surface water. This primarily affects aquatic animals, and through them, it can also affect humans. Among aquatic animals, fish are more exposed than aquatic mammals for a simple reason: fish breathe through gills, which have a very large surface area and are well-vascularized, making absorption of substances through the gills very efficient. An equilibrium between the toxicant’s concentration inside and outside the body can quickly be reached. Aquatic mammals, which breathe through lungs, can only absorb toxicants present in water through their skin or by ingesting particles or smaller animals that are contaminated. Indeed, humans are the last link in the food chain, and might be exposed to xenobiotics present in water due to the bioaccumulation and biomagnification process (see section exposure through food).

- Drinking water. In developed countries, drinking water quality is highly controlled, and there is no problem. However, it can be a significant source of exposure in developing countries. In the past, lead pipes were a potential source of contamination, though today, pipes and bottles are made of plastic, highlighting the fact of evaluating the risk of exposure to plastic and microplastic, as well as other substances, such as bisphenol A. On the other hand, in some countries, nitrate contamination of drinking waters are still a public health problem, especially for infants.

Exposure through air.

As a result of human activity, a wide variety of toxic substances can be found in the air. These substances can exist as gases or fine particles or aerosols. The most densely populated areas with higher industrial activity tend to have higher concentrations of toxins in the outdoor air. Conversely, in enclosed spaces, there may be elevated concentrations of tobacco smoke, car exhaust (in garages), paint fumes, etc.

This is especially relevant in case of work environment (occupational settings), where the population is exposed to different chemicals related to their professional activity mainly through air or dermal exposure.

More information on exposure assessment:

2.3. Risk characterization

Risk characterization is the qualitative and, wherever possible, quantitative determination, including attendant uncertainties, of the probability of occurrence of known and potential adverse effects of an agent in a given organism, system, or (sub)- population, under defined exposure conditions.

This is the phase in which data from hazard characterization and exposure assessment are integrated to quantify the risk. In general, if exposure data are above the HBGV, it can be consider that the specific population under study may be at risk. It is a scientific assessment that will help future decision-making (risk management).

The objective is to provide estimates of potential health risk in different exposure scenarios. Therefore, it must describe a) the initial assumptions and b) the nature, relevance, and magnitude of the risk.

Risk characterization statements should include clear explanation of:

- Any uncertainties in the risk assessment resulting from gaps in the science base.

- Information on susceptible subpopulations, including those with greater potential exposure or specific predisposing physiological conditions or genetic factors.

Risk assessment statements can be qualitative as for example:

- statements or evidence that the chemical is of no toxicological concern owing to the absence of toxicity even at high exposure levels;

- statements or evidence that the chemical is safe in the context of specified uses;

- recommendations to avoid, minimize or reduce exposure.

However, whenever possible, quantitative statements are preferable. Some examples are:

- a comparison of exposures with HBGV;

- estimates of risks at different levels of dietary exposure;

- risks at minimum and maximum dietary intakes (e.g. nutrients);

- margins of exposure calculation (see next subsection).

2.3.1. High risk populations

As mentioned above, another important aspect when assessing the risk is that not all individuals in a population are at the same risk. High-risk groups include:

- Workers in industries related to hazardous products, such as pesticides, paints, textiles, or chemical industries in general.

- People with high sensitivity, such as patients with chronic nonspecific lung disease.

- Children, due to their habits and possible enzyme deficiencies.

- Pregnant women, especially unborn children.

- The elderly, due to functional deficiencies.

This high-risk populations are normally studied separately to the general population during the risk assessment process.

2.3.2. Margin of exposure (MOE) approach

The Margin of Exposure (MOE) approach is a tool used by risk assessors to consider possible safety concerns arising from the presence of chemical substances in certain matrices (ex: food) when they deem inappropriate or unfeasible to establish a HBGV. According to EFSA, the two main situations in which this occurs are:

- when assessing substances that are neither genotoxic nor carcinogenic but for which uncertainty about their effects, e.g., due to insufficient toxicological data, does not allow for establishing a HBGV;

- when assessing substances that are both genotoxic and carcinogenic, in which case no HBGV can be established as any level of exposure could theoretically lead to cancer.

In the MOE approach, the toxicity thresholds obtained in animals (a NOAEL expressed in mg/kg/day) are compared with human exposure levels.

For example, if exposure occurs through drinking water containing 2 ppm of a xenobiotic, the exposure would be 2 mg/L of water. Assuming a daily water consumption of 2 L and an average female body weight of 50 kg, the daily exposure would be 0.08 mg/kg/day. If the NOAEL for nephrotoxicity is 400 mg/kg/day, the margin of exposure would be 5000.

Margin of Exposure = NOAEL in animals / human exposureMargin of Exposure = 400 mg/kg/day / 0.08 mg/kg/day = 5000

This large margin can be considered safe from a public health perspective. Low values indicate that human exposure levels are close to the NOAEL in animals. Since no safety factors are included in this calculation, values below 100 raise alerts for regulatory agencies to reconsider the risk assessment. Additionally, in the specific case of genotoxic and carcinogenic substances, the MoE value must exceed 10,000 to be considered acceptable.

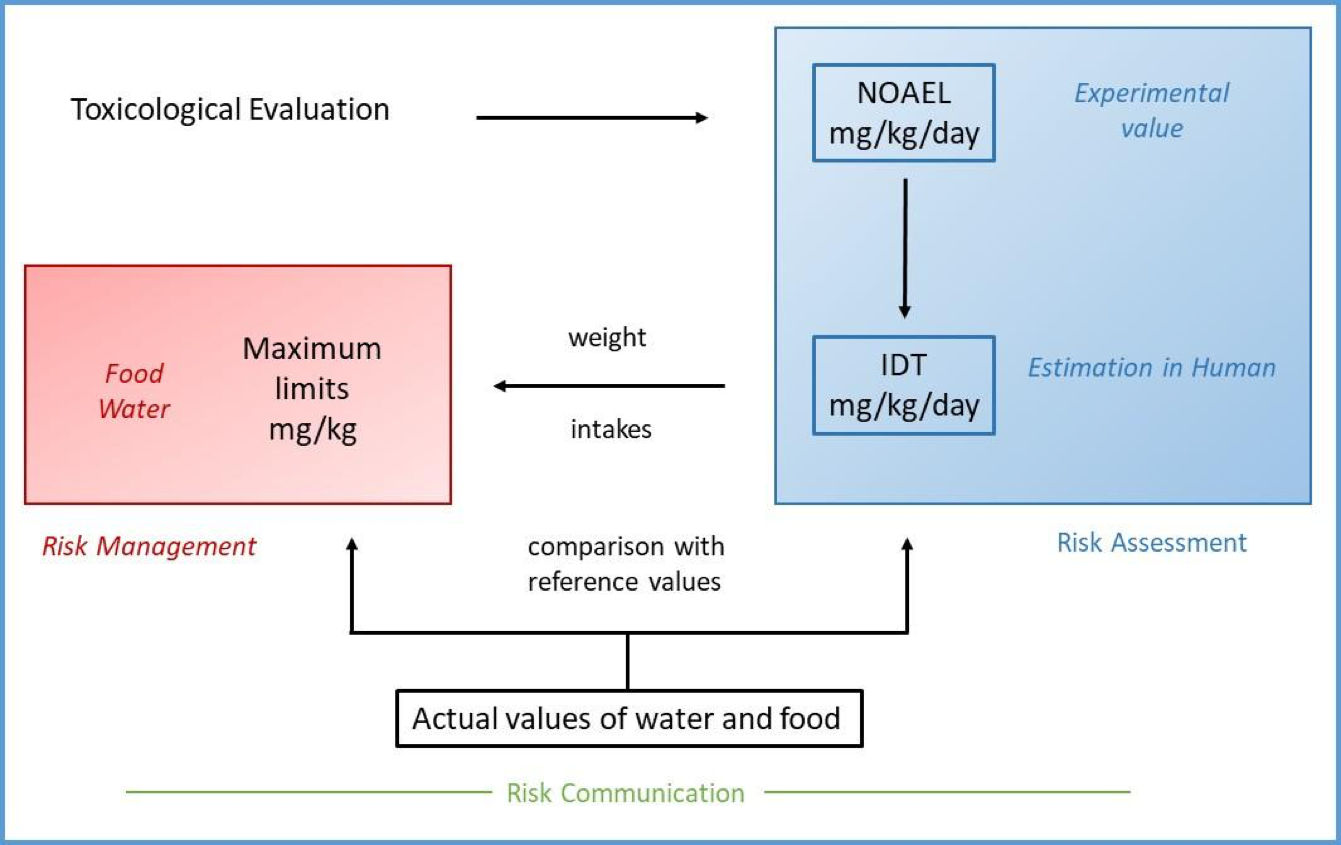

3. Risk maganement

The risk assessment process explained earlier is a systematic approach applied by scientists to predict risks to a specific population based on the available information regarding exposure and the toxicity of the compound. This type of analysis can lead to conclusions, such as the potential reduction in the percentage of affected individuals if exposure to a chemical agent is reduced to a certain level.

Based on the scientific information, if the results suggest that measures should be taken to reduce the population’s exposure to a toxic agent due to its potential toxicity, it is up to the appropriate authorities to make decisions. This phase is known as Risk Management. It consists of making political decisions, taking into account not only the results of the risk assessment but also other socio-political and economic factors, such as legal implications, economic costs, political repercussions, social interest, and the population’s risk perception. In short, it involves making a cost-benefit assessment. The final decision, considering these factors, results in the drafting of legislation and the establishment of control measures to ensure compliance.

Thus, the two components of risk management are legislation and control.

An example of risk management is the calculation of maximum limits (ML) for specific food contaminants allowed in a given medium (e.g., in a specific food), which are generally included in legal documents such as regulations or directives, making them legally binding. These maximum concentrations are estimated based on TDIs, considering the consumption rate of the food in question:

ML = TDI (mg/kg b.w) x weight (kg) / consumption (L or kg of food per day)

The complete and iterative process of risk analysis is summarized in Figure 6. This process involves three key components: risk assessment, risk management, and risk communication, each of which plays a critical role in ensuring public health.

It is also important to note that toxicological problems differ by country and era. Thus, what constitutes a risk in one country may not be in another, or what posed a risk at a particular time may no longer be a public health threat after several years. Generally, this is achieved by adopting measures aimed at reducing exposure. For instance, the prohibition of using tetraethyl lead in gasoline in Europe reduced lead exposure in highly contaminated areas, or the ban on smoking in enclosed spaces reduced the risk of lung cancer among passive smokers. These are all political measures (and therefore part of risk management) that have an impact on public health.

For more details about Risk Management you can access the following lecture.

Exposure to Complex Mixtures

This PBL case study focuses on one of today’s most pressing environmental health issues: exposure to complex mixtures of pollutants, specifically airborne particulate matter (PM). It challenges students to step into the role of a newly appointed health officer at a regional public health service in Maastricht (Netherlands), where residents living near a busy street express growing concern about air quality.

Students are tasked with organising a public information meeting to explain:

- What the government is doing to monitor air quality;

- How daily measurements of pollutants such as PM10, PM2.5, and nitrogen dioxide are carried out;

- How these values relate to health guidelines and legal thresholds;

- How to interpret health risks associated with repeated exposure to air pollution.

As part of their mission, students must also engage with the community to understand local perceptions of environmental risks and integrate this feedback using the “Risk Governance Framework.” This promotes a multi-stakeholder approach to managing complex risks in real-life scenarios.

Key learning outcomes include:

- Understanding the health implications of long-term exposure to air pollution;

- Interpreting environmental monitoring data and comparing it to regulatory standards;

- Applying risk communication strategies in a public health context;

- Using policy and governance models to improve environmental risk management.

This interdisciplinary case is ideal for students in toxicology, environmental sciences, public health, or risk policy, and invites them to tackle the challenges of real-world risk assessment and community engagement around complex chemical exposures.

Download complementary files:

(*) This file is for use by tutors/teachers and is password protected. If you are a tutor/teacher interested in using this case study, please contact us to get the password.

4. Risk communication

Finally, if risk management and control measures are taken, they must be communicated to the general population and to various social groups that may be involved, such as workers, consumers, lawmakers, environmentalists, etc. This process is known as Risk Communication, which falls not only under the responsibility of national health authorities but also frequently on international agencies, such as the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) or the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). Moreover, the communication process must be interactive between all actors: scientists, regulators, and society.

4.1. Risk perception

While communicating risk, it is very important to note that the perception of risk in a given population may not align with the actual risk posed by a specific xenobiotic. For instance, there may be a high perceived risk of pesticide exposure in food while having a low perceived risk of alcohol consumption, even though the latter may be higher in that society. Many social factors influence risk perception processes, which are also susceptible to manipulation through various means. Moreover, society, through political agents, decides the level of risk it is willing to accept. What one society deems intolerable may be acceptable to another.

In the following link you can access a video from EFSA explaining some aspects regarding risk communication and risk perception.

5. Risk assessment and safety assessment depending on the market authorization

As mentioned before Risk assessment is the process of estimating the likelihood and severity of harm caused by a product or its use under specific conditions. It focuses on understanding potential dangers (called hazards) and evaluating how exposure to these hazards might lead to adverse outcomes. This is normally done for contaminants.

However, for products needing pre-market authorization the Safety assessment of the product should be performed. Safety assessment determines whether a chemical product is safe for use under defined conditions. This process focuses on ensuring that the product meets specific safety standards and does not cause significant harm when used as intended (or under foreseeable misuse). Therefore, the compliance with these standards will depend on the chemical product, intended use, and therefore market authorization.

Some examples of Safety assessments are shown below.

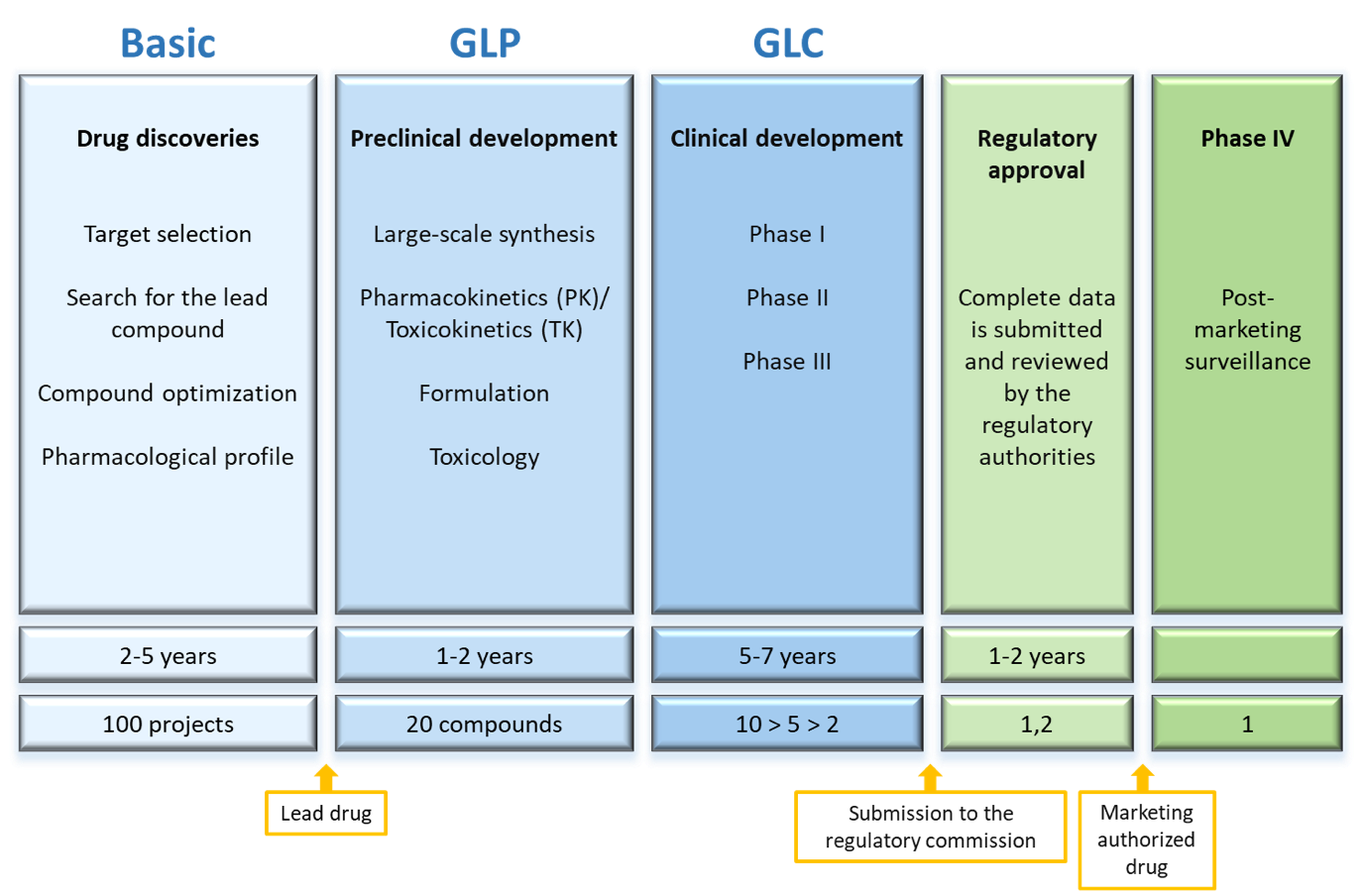

Safety assessment of pharmaceuticals

Pharmaceuticals represent a group of xenobiotics for which safety is best assessed. In the Research and Development (R&D) process of medicines, both efficacy and safety aspects are investigated all over the process (Figure 7). Before a new medicine can be tested on humans in clinical trials, a set of preclinical toxicity studies must be completed, determining the compound’s basic toxicity profile: its NOAEL, target organ, genotoxicity, etc. As the drug progresses in its development, additional preclinical toxicity studies are conducted, and possible adverse effects are studied in clinical trials.

Toxicity studies for regulatory purposes must be conducted under Good Laboratory Practices (GLPs) following OECD guidelines for toxicity studies and adhering to the recommendations of the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) concerning the type of studies required at each stage of R&D, their design, and interpretation of results. At the European level, the agency responsible for drug safety is the European Medicines Agency (EMA), while in the United States of America (USA) the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is in charge of it.

If a medicine is approved based on its efficacy and safety profile, while also considering quality aspects, and it is marketed, it remains under surveillance to detect any adverse effects through the pharmacovigilance system, which continues throughout the drug’s lifespan. Thus, the risk assessment (commonly referred to as safety assessment) of medicines is a process conducted by pharmaceutical companies. However, most companies have outsourced most of their regulatory toxicity studies to Contract Research Organizations (CROs). The companies typically retain simple initial screening studies, in vitro toxicity and genotoxicity assays, predictive in silico systems, or very short general toxicity studies. The longer and more complex studies conducted under GLPs (six-month toxicity, carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity, etc.), are generally outsourced. Nonetheless, proper interpretation and integration of these studies into the overall understanding of the drug’s toxicity require in-depth knowledge of the compound’s physicochemical and pharmacological characteristics, which the company is best equipped to provide.

Risk assessment in food safety

In the case of food, both intentionally added chemicals, which require pre-market and product safety assessment, and unintentionally present chemicals, such as contaminants, can be found.

Some examples are:

- Substances intentionally added to food for various purposes such as food additives.

- Compounds that remain as residues in food due to their use in production, such as pesticides used to promote plant growth, insecticides, herbicides or veterinary drugs used in animal health.

- Environmental contaminants that enter the food chain like heavy metals.

- Toxic products generated during the culinary or industrial processing of food, generally under high temperatures like benzo(a)pyrene or acrylamide.

In the European Union, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is responsible for ensuring the safety of all these types of compounds, while the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversees this responsibility in the USA.

Overall, food additives and pesticides today require a safety assessment process and subsequent authorization for marketing, similar to that of medicines. Many of them, in widespread use for many years, have received GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status. Regarding other compounds, risk characterization involves the steps previously described and requires obtaining toxicity data. The toxicity assays used are similar to those for pharmaceuticals, and the strategies applied for hazard characterization are defined by EFSA. Since in the case of contaminants, their management does not depend on authorization for marketing but on regulations and laws that set maximum levels (ML) in the various media where they can be found.

A video from the work carried by EFSA in this field can be found here.

6. Ecological risk assessment

An ecological risk assessment is the process of evaluating the likelihood that the environment might be affected by exposure to environmental stressors, particularly chemicals released into the environment. While the foundations of the process are similar to those used in human risk assessment, both hazard characterization and exposure quantification are more complex when applied to ecological systems.

For more information, visit the website of the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Environmental Risk Assessment of Pesticides: Terminaphos

This problem-based learning (PBL) case introduces students to the tiered approach used in Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) for plant protection products, as recommended by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). It simulates a real-world regulatory context in which a new pesticide—Terminaphos®—is proposed to combat Colorado potato beetles (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) that have developed resistance to conventional treatments in Southern Belgium.

Students are asked to assess the environmental impact of Terminaphos® using a stepwise methodology:

- Tier 1: Screening-level risk assessment based on physicochemical properties, core toxicity, and exposure data;

- Tier 2: Probabilistic approach using species sensitivity distributions (SSDs);

- Tier 3: Higher-tier assessment based on mesocosm (field-like) experiments.

Working in stakeholder groups with different perspectives (e.g. regulators, industry, farmers, NGOs), students must analyze the available data, debate the risks and benefits, and reach a decision about whether Terminaphos® should be authorized. The scenario also allows for the integration of socio-economic and geopolitical considerations alongside scientific data.

Key learning outcomes:

- Understand the physicochemical and ecotoxicological properties of pesticides;

- Evaluate experimental data from lab and field-based studies;

- Apply tiered risk assessment frameworks following EFSA guidance;

- Explore the role of stakeholder input and socio-economic context in regulatory decision-making;

- Develop critical thinking, data interpretation, teamwork, and science communication skills.

This interdisciplinary PBL is ideal for students in toxicology, ecotoxicology, environmental sciences, and regulatory affairs. It provides both scientific rigor and policy relevance in addressing the environmental challenges posed by pesticide use.

Download complementary files:

References and notes from the authors

The aim of this document is to give a simplified overview of the risk assessment process for undegraduates and master levels students. For more detailed information there are several documents from recognized international organizations that can be consulted. Here you can find a non-exhaustive list of documents and websites:

In addition, the lectures of the advanced course will broaden your knowledge on Risk assessment and how to apply it to various cases on complex exposures and emerging risks.